“… an allowance is made for interlacing.”

Stebler and Schröter’s 1889 handbook on grass and legume species and mixtures. Their method of estimating seed rate for each species in a mix. Was the recommendation of over-seeding justified? Lessons for regenerating complex forages today. An article in the series on crop-grass diversification.

Imagine … you’re making a complex seed mixture by combining seed of each of the constituent species or varieties. You work out the best combination of species for the field – three or four for one-year’s hay and maybe 15 for long-term pasture – then gauge the ideal proportion of each in the resulting hay or pasture, e.g. 20% ryegrass, 10% red clover, and so on up to 100%.

It was a complicated task. The composition of each species – in terms of protein, fat, fibre and so on – had to be known so that the mix would satisfy the purpose, whether hay or pasture, sheep or cattle. The amount of nutrients that each species would need from the soil had to be estimated. For example, a nutrient-demanding species might have a hard time in a nutrient poor soil or else starve other, less demanding species. Then the proportion of each species in the mix had to be calculated. And all this before science and farming were fully aware of soil-plant processes such as symbiotic nitrogen fixation.

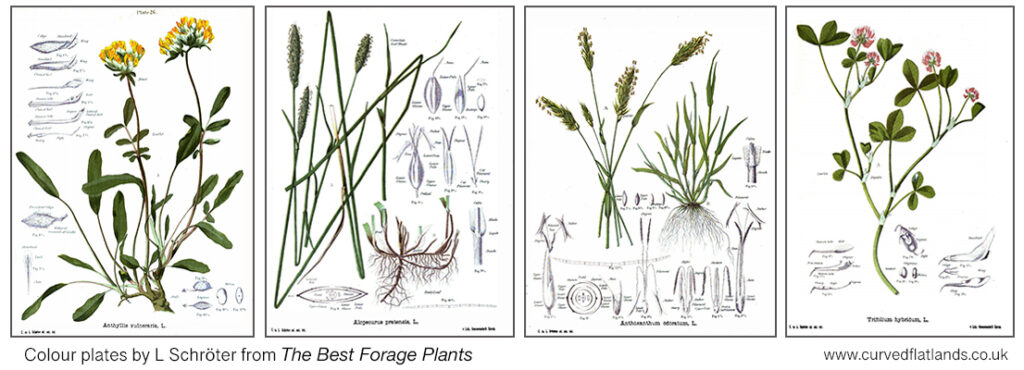

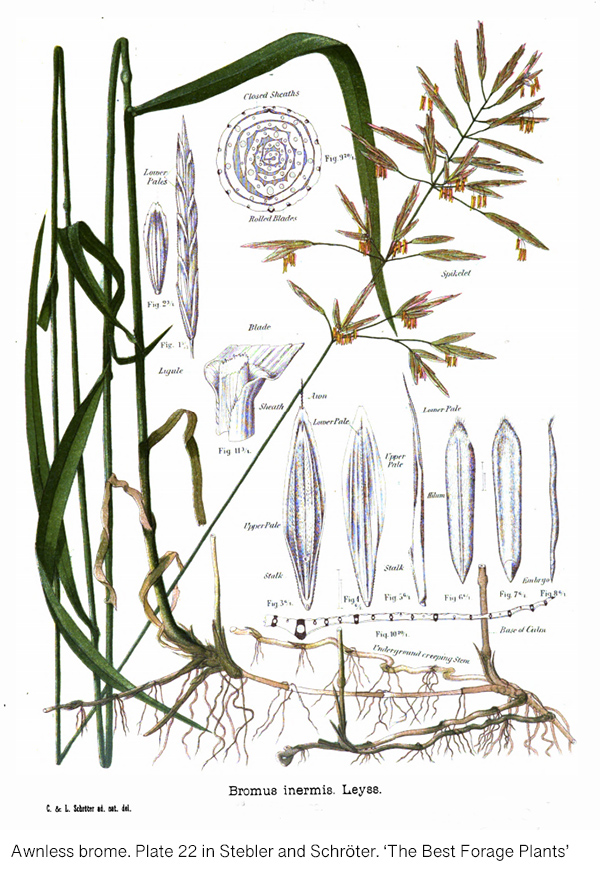

A major contribution to knowledge at that time was the work of FG Stebler in Switzerland. His book – The Best Forage Plants [1] – was written in German, co-authored by botanist C Schröter, translated into English by McAlpine [2] and the translation published in 1889.

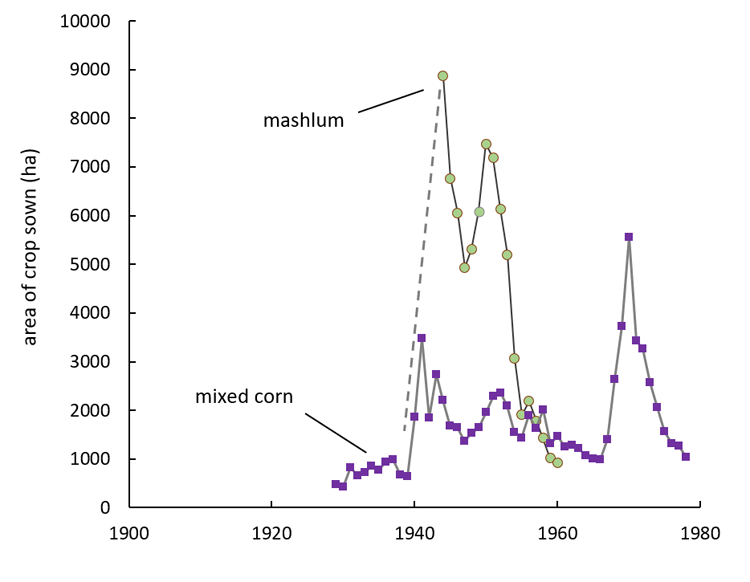

There was great interest in grass-legume mixtures at that time. A shift from arable to grass had begun in Britain, initiated by serial bad weather and crop failure, coupled with unbridled cheap corn imports from the USA. It was the start of a long-term slump in arable farming and a rise in pasture husbandry [3].

The book described 30 species in detail: 21 grass and 9 legumes. Most would have been familiar in mixtures used in Britain, with few exceptions such as the legume Galega officinalis which they named Officinal Goat’s-rue (‘officinal’ because of its medicinal use in parts of Europe).

How much seed of each grass and legumes species for a mixture

Stebler’s recommendations on seed rate (weight per acre) were not without controversy. He worked out from many field trials the seed mass of each species that would be needed to cover and produce good growth on an acre of field: for example, 38.6 lbs for perennial rye-grass, 18.5 lbs of cocksfoot, 22 lbs of lucerne and 15.8 lbs of red clover. (To convert to today’s units, 1 lb is 0.454 kg and 1 acre is 0.405 hectare.) So 7.72 lb of perennial ryegrass seed would be needed if its proportion was 20%.

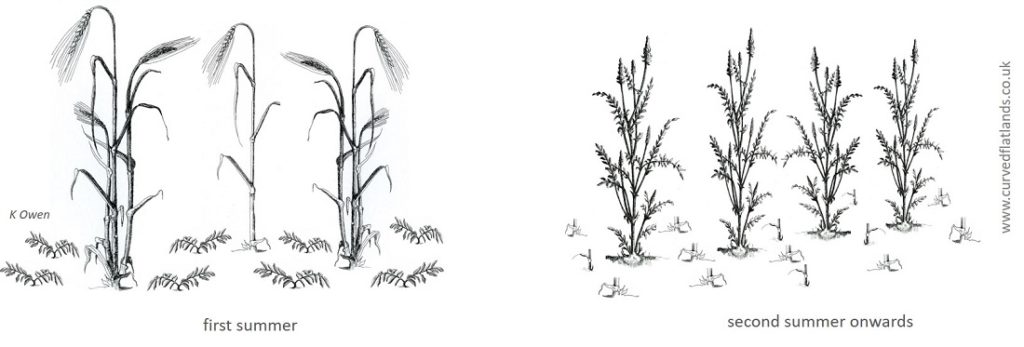

His method went further by recommending that more seed of each component should be added than estimated by such simple proportion. The extra seed ranged from 10% to 80%, but was typically 50%. The reasoning was that the species in a mix occupy different parts of the space: roots exploring either deep or shallow soil layers, for example; or some species leafing early in the year, others later.

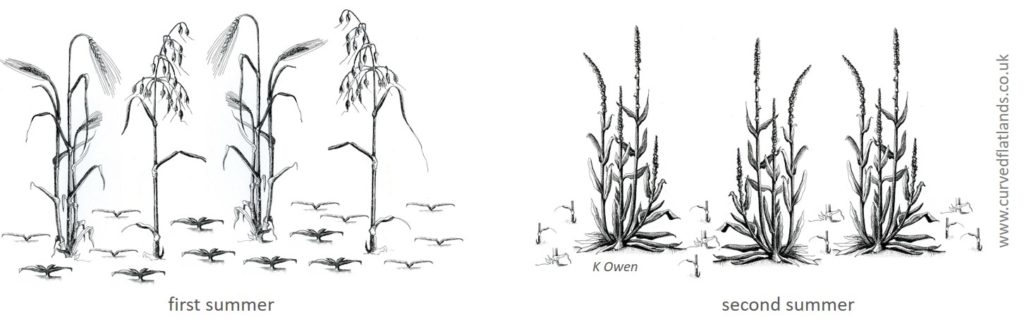

This is what Findlay [4] in 1925, commenting on Stebler, meant by interlacing. The quote at the top of the page, from Findlay reads “As the roots and leaves of the different ingredients do not occupy the same places …. an allowance is made for interlacing.”

Grass specialists appreciated that roots and leaves of different species interlace: they enter each other’s space, they co-occupy ground. Several species might occupy the same area of ground but in doing so they are not always competing for the same resource or if they are then it is not in the same place or time.

Is overseeding a waste?

Findley appreciated what Stebler meant, but went on to criticise the method. He wrote “at no time is there any connection between the proportion of the seeds sown and of the plants either in the hay or in the pasture”, and gave the example that a competitive grass will oust an uncompetitive one regardless of the proportions in the mix.

Findlay was right in principle: the extent and type of interlacing depend on how the species react to each other in the local conditions. Yet over-seeding is not without merit. The aim of a seed mix was to get more mass or nutrition than could be had from any species grown alone. Stebler said that to do this you had to sow more seed of each component than that based on simple proportion.

Take the very simple example of a 50:50 mix containing one grass or cereal and one legume. The legume fixes its own nitrogen (N) from the air, so will take little from the soil. Consequently, the cereal or grass has most of the soil N to itself, but if it were only sown at 50% of what it would take to cover the ground alone, then it might have a hard time extending its roots to get the N throughout the whole soil space, which includes that ‘under’ the legume. Therefore (Stebler would say) it should be sown at more than half the seed rate needed to grow it alone.

That’s not the full story because the two species would also compete for other resources – solar radiation, water, the macro- and micro-nutrients. In a 15-20 species mix for permanent pasture, very many interactions would occur between the types, and some would result in the elimination of species. The ones that went would not be the same in all soils and climates. One purpose of a mix therefore was to build in redundancy, such that the mix would still perform well even if some components disappeared.

Postscript – Stebler’s influence ?

In his preface to the translation into English, McAlpine had the view that Stebler & Schröter, now accessible to English readers, would be seen as a major work of agriculture, leading to ‘a revolution in the forage culture of Great Britain’. Further on, he writes ‘I do not hesitate to affirm that if Stebler be destined as I believe he is to become a power in agriculture the effect will be to increase the production of good forage and to improve the practice of this most important branch of farming.’

Yet Findley in 1925 [3] found Stebler’s methods deficient in several respects and did not endorse them. Whatever Stebler and Schröter’s influence on British forage might have been in the 1890s, it did not last. After the mid-1900s, mineral fertiliser would come to supply most of the nutritional needs of grass and supplant forage legumes such as clovers and trefoils. As described elsewhere, the diversity of grass forages became poor and probably the knowledge of how to manage multi-species grassland faded [5].

Recent decades have seen a part-reversal of that trend, in that grass-legume mixtures are increasingly available from seed merchants. Some of the mixtures are intended for grazed swards but the emphasis seems to be on restoration for wildlife conservation.

The lesson from Stebler is that the basis of estimating seed rate in a mixed crop or pasture might need to be reconsidered. In many parts of the world, however, seed is not plentiful. The choice has to be made: eat the grain now or keep it to sow for the next crop.

To come …. More on Stebler & Schroter’s Tables on the nutritional value and needs of grass versus legumes.

Sources / references

[1] Stebler FG, Schröter C. ‘The Best Forage Plants’. Translated into English by A N McAlpine, 1889. Publisher: Nutt, London. Available to read online through Google Books. The illustrations of grasses, some reproduced here, were by L Schröter, brother of the second author. A review of the book, Wrightson J. (1889). A Review of The Best Forage Crops. Nature 39, 578-579, tells readers that the treatise omits the common fodder crops such as vetches and brassicas, and deals mainly with pasture grass mixtures.

[2] A N McAlpine, the translator of Stebler & Schröter into English, was Professor of Botany, New Veterinary College Edinburgh and Botanist to the Highland and Agricultural Society.

[3] curved flatlands article: Food security in the pandemic.

[4] Findlay, W M. 1925. Grassland in Scotland. In ‘Farm Crops’ edited by W G R Paterson. The Gresham Publishing Company, London.

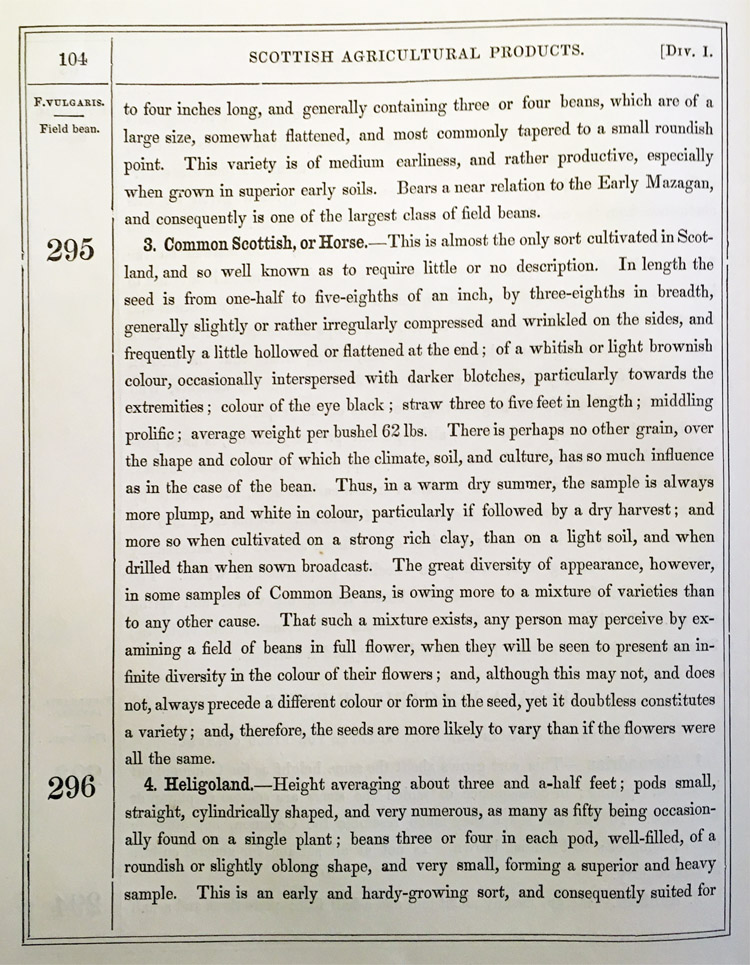

[5] curvedflatlands articles: Grass mix diversity a century past – for reference to books by RH Elliott and H Stevens; and 1800s mixed crops – lessons from the Agrostographia – gives examples of the Lawson’s (Edinburgh) crop and grass mixtures.

Acknowledement Thanks to K Owen for allowing the use of her depictions of interlacing on Pictish symbol stones.