Early 2018 and Dundee’s waterfront is shaping well. The various cafes, restaurants and bars are gearing up for the opening of the V&A museum later in the year and locals will be dusting off their sun hats in readiness for long evenings dining by the waterside. Yet now in March that seems improbable. The winter 2017-18 has been colder than usual, temperature persistently below and around zero for months.

But which Dundee can we see here in these photographs? Not quite the Dundee as we know it – the one 7 miles from the Living Field garden [1], even with the tall ship and strange looking building by the waterfront … and the heavy cloud about to drop its load of water.

No. This place is somewhere warmer. A full-grown palm tree gives it away, and then the dark, flat line of a mangrove forest, half in the water. Mangroves couldn’t grow by the Tay, not before some serious warming. This is not cold, wet Dundee at 57N but a warm and monsoonal Queensland at 17S.

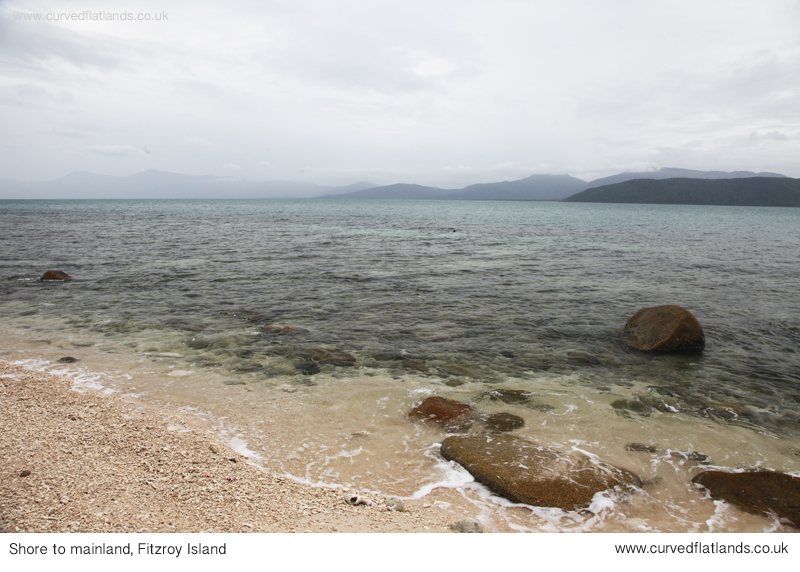

We were out from Cairns, looking back towards the waterfront from a boat to Fitzroy Island, named by Captain Cook after a member of the nobility, not Robert Fitzroy, the eminent meteorologist who captained the HMS Beagle that took Darwin on his voyage round the world [2].

Fitzroy Island

Fitzroy Island lies in the inner Great Barrier Reef, a small island, surrounded by warm water that supports vibrant corals and fish within easy snorkelling distance from the beach. The corals and sea life were astounding, and one of our party even swam with a wild turtle.

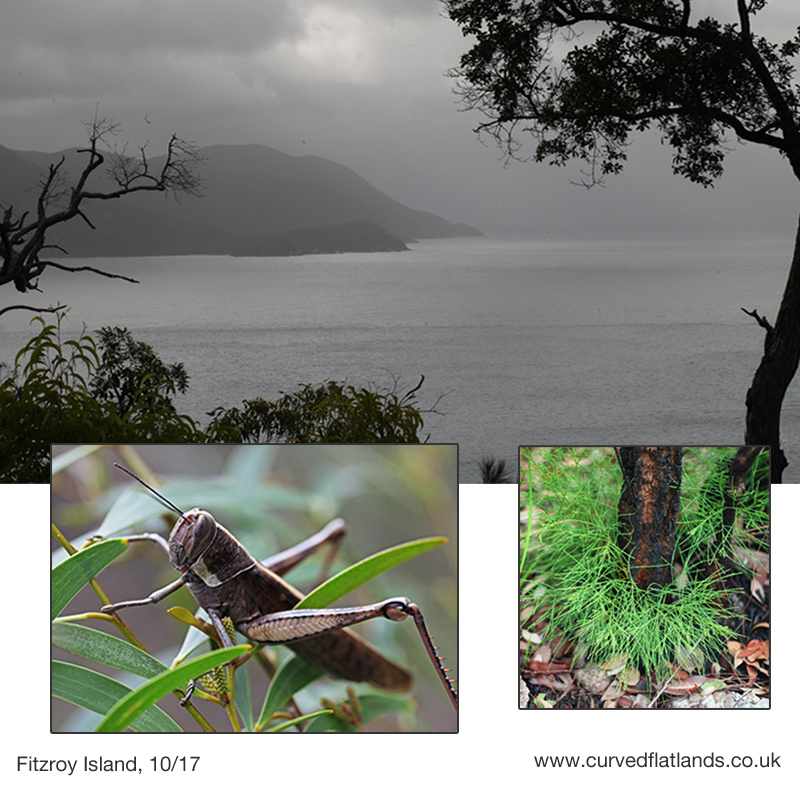

The island rises from the shore to a rocky peak over a couple of miles, forming a gradient of soil depth and exposure over which the land plants varied according to their needs and capacity to survive. Pandans and casuarina fringed the beaches, the dense forest behind merging into dry woodland and scrub on the higher land in the centre of the island.

Fire had blackened much of the vegetation on this higher land, yet adaptation to periodic burning was evident in the form of leafy shoots emerging from singed turf and dead-looking stems.

The Great Barrier Reef is under threat, notably through bleaching of the coral [3]. Plastic also has its insidious effect here as in many places. The seas round the island looked fairly clear of it. The wind and tides brought a few pieces of waste onto the beaches, but they were being picked up and binned by visitors.

Even here

The problem here is not so much the large mass of waste being washed up on the beaches, as happens in parts of the West Highlands of Scotland for example. The reef is habitat to six of the world’s seven marine turtles. If a single piece of plastic is ingested by a turtle, it is unable to function and floats on the surface, where unless rescued, it weakens and dies.

Turtles can live for many decades but the Green Turtle, for examples does not breed before 45 years [4]. Its populations – though showing no evidence of decline – are said to be imbalanced towards females, a change attributed to increasing temperature in the nest.

A turtle sanctuary and rehabilitation centre on the island and on the mainland at Cairns looks after damaged animals, removing the plastic by feeding them until the stuck piece passes through and then nursing them until they are strong enough to be released [4]. To be rescued, a floating turtle has to be seen by a passing boat, and one sympathetic to its plight. For every one rescued, many others are likely to die.

The Great Barrier Reef and Scotland’s coasts therefore share more than primal beauty and a claim to wildness. The millions of bite-sized plastic pieces on the Scottish beaches referred to in the Living Field article Colours of Silverweed [5] are of a size to be swallowed by a turtle. It’s almost a relief that the plastic bits managed to find their way to our coasts, and settle themselves for a while among the shingle.

Neither place can do much to stop the plastic. The origins of most of it are many thousands of miles away. Even if the entry of new waste into the seas was reduced on a global scale, which is unlikely to happen for decades, the plastic already there will still circulate, get washed up or be eaten. Despite some complacency that the problem is soon solvable [6], all that can be done at the point of receipt is to continue limiting its damaging effects.

A long period of habitation

There is geological evidence that Fitzroy Island and other similar islands were once connected to a mainland until rising sea levels towards the end of the last Ice Age cut them off. This is another north-south connexion since the effects of the melting of ice covering northern Europe were to raise sea levels here and around the world [7].

People had been living in Queensland for tens of thousands of years before that time. The mainland and the island would have been part of the same land mass. Improbable as it may seem to us in Europe, there is evidence that the people have kept alive the memory of the rising sea level through their spoken traditions [8].

Sources and further information

[1] The Living Field Garden is located at the James Hutton Institute, near Dundee, and is a place to study the crops and wild plants, past and present, of lowland Scotland: www.livingfield.co.uk. The new V&A museum is sited by the Tay estuary in the centre of Dundee.

[2] The island had aboriginal names before James Cook named it FitzRoy in 1770. Naturalists and meteorologists are likely to know another FitzRoy – Robert Fitzroy (1805-1865) – as the captain of the ship HMS Beagle that took Charles Darwin on his voyage round the world. Robert FitzRoy was also a pioneering meteorologist, whose name replaced Finisterre in the Shipping Forecast in 2002. (Met geeks will have stayed awake to hear the first ‘Fitzroy’!) For general information on the island, try the Queensland Government web site on Fitzroy Island National Park.

[3] Great Barrier Reef: for background and research, see ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies, and a YaleEnvironment 360 article published 2017 A close-up look at the catastrophic bleaching of the Great Barrier Reef. The ARC web pages described other harmful effects of plastic on the Reef’s ecology.

[4] Information on the Green Turtle is given at the GBR Marine Park Authority’s web site. The Cairns Turtle Rehabilitation Centre describes the many ways that turtles can be damaged by human-made objects, including getting tangled in nets and being hit by boats, as well as by ingesting plastic and other waste.

[5] Colours of Silverweed [link available soon] is a Living Field article, describing the truly astounding amount plastic pieces accumulating on some of Scotland’s finest beaches, coves and inlets; and also what people are trying to do to remove it.

[6] Several newspaper articles and posts towards the end of 2017 implied that if action is taken now by governments across the world then the problem of plastic waste would disappear. One such was a leader in The Times newspaper of October 6 2017 with the title Rubbish Dumped and the strapline “The world’s oceans are being choked by plastic, but they will recover quickly if governments work together to stop it reaching the open sea”. Here, ‘recover’ and ‘quickly’ need to be reconsidered. There is no short term solution.

[7] Current predictions of sea level rise in the 21st century are compared with the much greater disturbances towards the end of the last Ice Age in an information piece by the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority at Impacts of Sea Level Rise on the Reef. There is also a link on their web site to further information on ‘Marine Debris’.

[8] For example, see the following article in the online journal The Conversation Ancient Aboriginal stories preserve history of a rise in sea level.

[9] Views on the origins and distinctness of some of the peoples of the Queensland rainforest are highly contentious. See the article by Peter McAllister in The Weekend Australian, January 2011 – The ‘short mob’ goes back a long way. The 2002 article by Keith Windschuttle and Tim Gillin can be viewed with footnotes and references at The Sydney Line.