SEDA Land’s mapping initiatives. Communities, landowners, science, technology, computer gaming. Food sourcing and food security. Local vs global. Spatial data and the need for local knowledge. Building resilience to global disruption.

SEDA Land arose from the Scottish Ecological Design Association’s 2021 Land Conversations as an active and inclusive grouping intent on exploring and then influencing the way we value and manage land and water [1].

One of the first developments from the Land Conversations was an idea to ‘map’ the land around a place or community for its capacity to provide for the people, now and in the future. That capacity included food, water, wood, open space and a sense of place. The ideas quickly developed and by early 2022 took form through collaborations between many people and organisations in a project called Mapping Future Food and Climate Change.

Community – land – science – art – gaming

A pilot study began in 2022, based on the locality of Huntly, comprising a range of community groups, schools and local landowners [2]. Scientific institutions are providing knowledge of soil, crops, food, carbon storage, greenhouse gas emissions [3] and expertise in computer gaming [4]. The main elements of the pilot study are as follows.

- The land in and surrounding the town, and its nature, shape, occupancy, community involvement and ownership.

- The biophysical status of the land, its climate and weather, bedrock and soil, carbon storage, biodiversity.

- Structure of the land – mapping ‘parcels’ or units of management (e.g. fields, woods) and what they produce or contribute.

- The community’s use of locally-grown products versus the import of things grown on resources elsewhere.

- The meaning of the land to the people, expressed through tradition, art craft, music [1].

- Definition and analysis of spatial and temporal ‘layers’ (e.g. area, soil, climate, use, inputs, outputs) to understand the current value and limitations of the land and its future potential for delivering benefits such as food security, C sequestration, biodiversity and community involvement.

- Expressing all of the above through computer gaming.

But where do we begin … ?

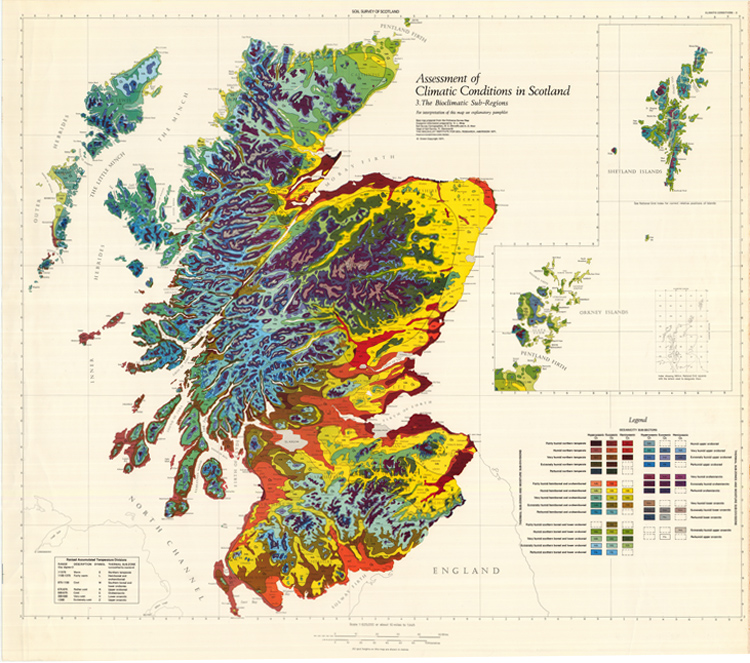

Mapping the biophysical, economic and political landscape of Scotland has a history going back several hundred years. The climatic maps produced in the early 1970s from the Macaulay Institute for Soil Research (Fig 2) are among the most spectacular. The arable-grass agricultural land lies mostly in the red and yellow areas around the east coast and across the central belt.

In the half-century since Fig. 1, digital maps have become the norm, now available online for many features – including land classification, soil and soil carbon content, erosion and compaction risk, and land suitability for agriculture and forestry [6]. The study based around Huntly will be able to use the maps, and the data behind the maps.

Mapping land and land use

The patterning of the land is one of the first things to appreciate, and in particular the division of the land into the units of management. Why is this important? Well … suppose three fields have similar soil, slope (etc.) but one is woodland, another is grassland and the third is cropland. They all differ in what they produce, their agrochemical and mechanical inputs, the carbon they store, the biodiversity they support and what they conserve or release to the wider environment. Therefore the management of the field is just as important as its underlying qualities.

Mapping fields and other land parcels in fine detail is now possible (Fig. 2). Their shapes can be made visible and to a large degree, but not completely, the use of the land in each parcel can also be defined. Without even visiting the area, the parcels containing established vegetation such as woodland and marsh can be identified from remote sensing and each of the agricultural parcels can be separated into grassland and arable (or cropped land) using data from government census.

The sequence of crops grown in an arable field can also be defined, and from that, combined with data on soil, climate, outputs (yield, etc.) and inputs (agrochemicals, etc.), the capacity for carbon storage end emissions can be estimated or modelled.

Let’s get on with the mapping.

Given the right information [7], the shapes can be coloured to show the different forms of land use. In the example in Fig. 3 – based on the field patterns in Fig. 2 – the first to go in is grassland (Fig. 3 left), then tilled or arable land (centre) and third, the remaining areas consisting of woodland, vegetables and fruit, minor crops that occupy relatively few fields, and also semi-natural vegetation (right).

When all land parcels have been identified, the map looks as in Fig. 4: a complex mosaic of land use types that gives the Atlantic zone maritime its unique features. Some of the patterning originated hundreds, even thousands of years ago. Like much of lowland Scotland, and despite removal of the original vegetation, the fields are diverse in size and shape, with little evidence of prairie agriculture that continues to degrade so much once-natural land in many parts the world.

Limits to data – the need for local knowledge

Because of the way land use has been recorded historically, the arable fields can be defined by the crops grown in them, such as barley, oats, wheat, beans, peas, oilseed rape, potato, turnips, and so on. However, grassland – which often occupies the most land in regions of lowland Scotland – tends to be lumped in just a few categories. In the current census, the two categories are grass present in a field for under 5 years and grass in its fifth year and over. This lack of definition in grassland obscures the great variation found across Scotland’s managed grass in terms of biodiversity, soil carbon content, fertiliser inputs, greenhouse gas emissions and grazing potential.

Several other factors important for the study cannot be gained from current surveys. It is not possible to know from remote sensing or census data the quality and purpose of the product and whether it is consumed locally or exported from the area. For example, a field of cereal (barley, wheat or oats) could be used for malting (alcohol), livestock feed or milling to produce flour. The cereal feed might be given to livestock on the same farm or sold to a merchant to be used in another place. Even much of the grain used for milling – though small in quantity compared to malting and feed – will be sold to merchants for distribution elsewhere.

And it’s not possible to know what the landscape means to the people who live in the area. So for these unknown or uncertain features, we must add in local knowledge ….. that provided by the general community and the people that manage the land.

Next steps

SEDA Land, the Huntly Community interests and the academic partners are now looking to obtain grant funding. In the meantime, several of those involved will be scoping the digital mapping and other background data available online and members of the mapping group (1-4] will be getting to know each other through meetings, real and virtual.

By way of introduction to the project, SEDA Land is preparing a set of questions asking people’s perceptions of what the land around Huntly provides – for example, how much food and timber is grown locally rather than imported. The questions are intended primarily for schools but will be available to any in the community.

Spatial scales and land categories

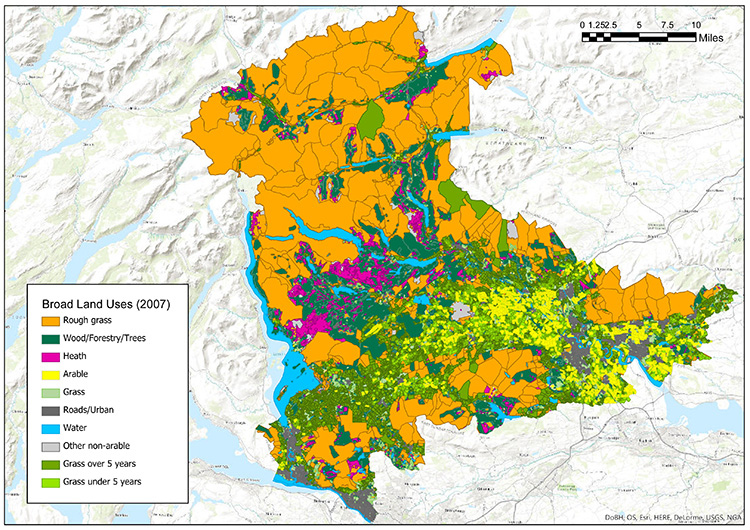

One of the first things the group will consider is the spatial scales at which data will be recorded and the categories into which land is divided. An example of broad land use categories is given in Fig. 5, which represents a tract about 30 miles at its widest. This sort of mapping gives a quick guide to the general possibilities for food and timber production. Green and yellow is already under managed agriculture. Orange, which covers more than half the area, is of low productivity, mostly used for extensive grazing of sheep, but offers possibilities, for example, of woodland regeneration.

Much finer detail can be defined, as in Fig. 2-4, giving clues as to how local topography, soil, microclimate and past management determine the patterning of fields and what can be grown in them.

The fields and other units in a tract of land a few kilometers wide are shown in Fig. 6. The area to the bottom of the image, comprising many small fields, has been in agricultural use for thousands of years, but records exist of its conversion into high-quality arable and grass from the time of the monastic improvements beginning in the 1200s. The top of the image is higher land which would have been woodland in prehistory, but now comprises large units of open moor or rough grazing. The strands of small fields running down from the moorland identify water courses. Fig. 6 is taken from the upper left of the larger area shown in Fig. 7.

The scientific contributors will assist with defining scales and data, but anyone with interest in the project can begin now with online and free-to-use mapping through the National Library of Scotland and Ordnance Survey [8].

The curvedflatlands web site will be publishing further news, posts and comment over the coming months and maintains a growing inventory of relevant data sources [9]. The SEDA Land web pages [1] will be the formal point of contact for the project.

Sources | Links

[1] SEDA Land is part of the Scottish Ecological Design Association: https://www.seda.uk.net/seda-land. A working group within SEDA Land, including all the participants, is taking forward the work on community mapping. Primary contact for the project: Gail Halvorsen, email: gail@halvorsenarchitects.co.uk. As in the Land Conversations, writing, poetry, art, craft and music will be integral. Contact: Sophie Cooke (sophie.cooke1@open.ac.uk).

[2] Primary contact: Huntly Development Trust www.huntlydevelopmenttrust.org. Email: Jill Andrews (jill.andrews@huntly.net). Local schools and landowners are active in the project.

[3] The scientific input is guided by the James Hutton Institute and Scotland’s Rural College (SRUC). Contacts at JHI: Lorna Dawson (lorna.dawson@hutton.ac.uk) and Cathy Hawes (cathy.hawes@hutton.ac.uk). Contact at SRUC: Mads Fischer-Moller (Mads.Fischer-Moller@sruc.ac.uk).

[4] The University of Abertay, Dundee, will be working towards gaming design through a post-graduate student group starting later in 2022. Contact: Kenneth Fee (k.fee@abertay.ac.uk).

[5] E L Birse and colleagues at the Macaulay Institute for Soil Research (now part of the James Hutton Institute) produced three classic maps on the Assessment of the Climatic Conditions in Scotland. The one shown is the last of the three, credits as follows:

[6] The James Hutton Institute’s online resources: Scotland’s Soil Data and other maps accessible from that page .

[7] Data for defining land use (crops, grass, etc .) in Fig. 3, 4, 5, 6 and 7 came from EU’s Integrated Administration and Control System (IACS) and was spatially analysed by Nora Quesada, Graham Begg and Geoff Squire at the James Hutton Institute. The maps in Fig. 4 and 7 were published some years ago on the Living Field web site at Scaperiae. Contact: graham.begg@hutton.ac.uk.

[8] Online map resources The National Library of Scotland has an increasing range of historical maps available online at the Map Images Homepage. The Ordnance Survey’s extensive downloadable resources are at Open Data Downloads and for education, see Free Education Resources for Teachers, and Digimap for Schools.

[9] curvedflatlands is compiling an inventory of mostly online data on land, soil, vegetation, biodiversity, climate, etc., which will be updated as new material becomes available: Sources of Information.

Author / Contact: GS has been working with SEDA to develop the 2021 Land Conversations, is on the steering group of SEDA Land and keeps (honorary) links with the James Hutton Institute. email: geoff.squire@outlook.com or geoff.squire@hutton.ac.uk

[Page online 10 March 2022, minor edits 27 March 2022]