The prescience of art

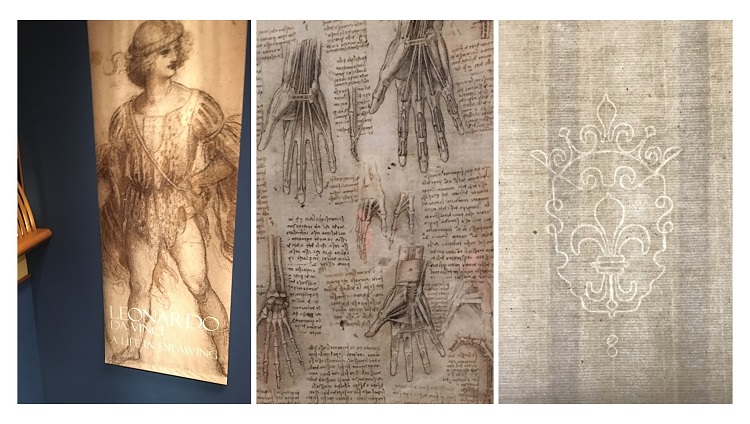

Two art exhibitions were visited – coincidentally – during preparation for Invading the Skin. The first was of Leonardo Da Vinci’s drawings on view at Edinburgh. The second was a major display of William Blake’s art at Tate Britain in London, in particular his workings around Dante’s Divine Comedy.

Da Vinci’s cataclysms

The exhibition of Leonardo Da Vinci’s Drawings at The Queen’s Gallery, Holyrood, Edinburgh, 22 November 2019 to 15 March 2020, marks the 500th anniversary of his death. The drawings are arranged around the walls of the exhibition rooms in groups that contrast the fine detail of his botanical and zoological anatomies with destructive deluges and storms. It’s like he’s saying here’s the exquisite beauty of evolved life forms, but they can be erased in a instant.

The drawings are laid out in the book by Clayton (2019). Botanical studies include common species such as oak, bramble and sedge. In one of them Da Vinci places two dye plants on the same sheet – oak and dyers greenweed (1506-12), these same species now growing close together in hedgerows and Living Field garden at the James Hutton Institute near Dundee. Human anatomical studies include limbs and muscles, the heart and lungs, and The fetus in the womb (c. 1511). Some were based on dissections of recently dead people.

But trouble’s not far away! Concern about the state of humanity appears in A cloudburst of material possessions (c. 1506-12) in which everyday objects drop from clouds and lie strewn across the ground, a lament against materialism it seems. Then come the cataclysms, drawn near the end of his life.

Clayton (2019) cites some of the wording from Notes and sketches of a deluge (c. 1517-18), which comes nearest the subject of Invading the skin of the earth. Da Vinci writes of a mountain: ‘From its sides the soil slides together with the roots of bushes, denuding great areas of rock.’ And later –

The bases of the mountains are covered with ruins of trees hurled down from their lofty peaks, mixed with mud, roots, branches and leaves thrust into the mud and earth and stones.

More storms and deluges follow, the earth and its inhabitants at the mercy of (super?)natural forces: fires raining down from thunderclouds, palls of smoke and fire, boiling seas, skeletons rising from graves, all described in Apocalyptic scenes and with notes (c. 1517-18).

There is no allusion as to whether the the cataclysms were entirely unavoidable or the result of chronic, man-made degradation. Some are certainly unavoidable, yet the cloudburst of material possessions suggests he was aware of the link between materialism and the possible end of the world as he knew it.

William Blake’s Fire and Ice

The exhibition of William Blake’s art at Tate Britain in London displayed many works, both those familiar from books and postcards like Newton and ones not widely known such as illustrations to The Grave and wood engravings of farming scenes and husbandry. With Blake, you might be in sublime landscapes but you are never far from consequences and destruction, the end of it.

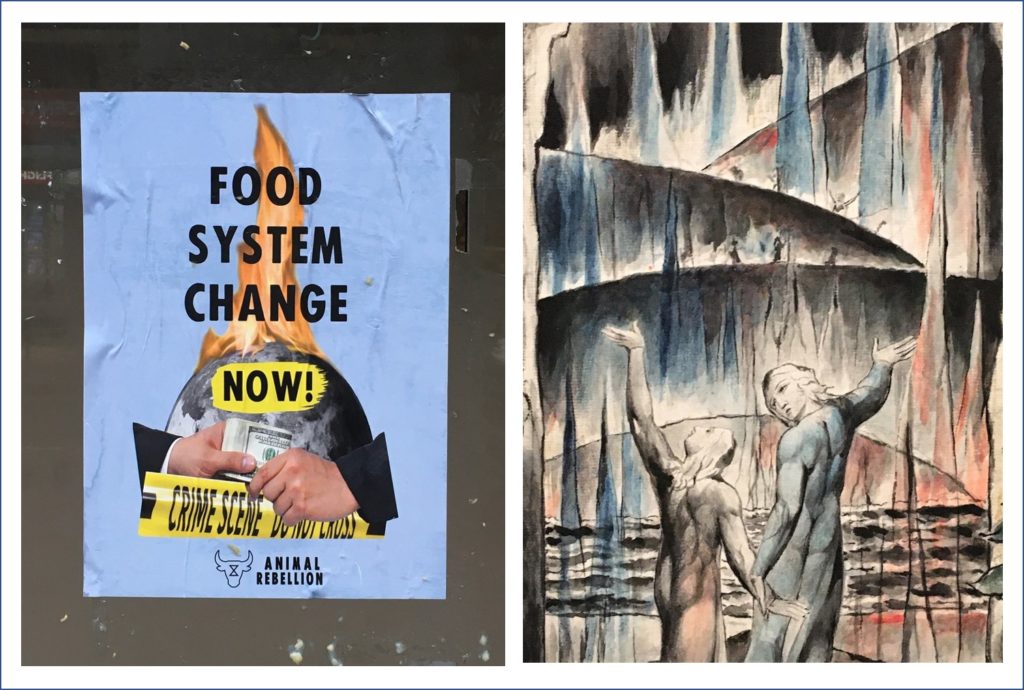

Three of the works are shown in the panel above. Those at the left and right are classic Blake (seen ‘live’ for the first time) but it was the series of works illustrating Dante’s Divine Comedy that were the revelation. The one in the centre above shows the poets Dante and Virgil at Hell Gate (1824-27) with the famous inscription, which differs with every translation, about abandoning all hope. Blake’s many drawings for the Divine Comedy were assembled in a recently published book (Schutze & Terzoli, 2019), so it was timely to see a sequence of them at the exhibition.

In the Divine Comedy, Dante (1300-), in a mid-life crisis, gets lost in a wood, to be found by the Roman poet Virgil (born 70 BC) who then takes Dante on a journey through Hell, Purgatory and on to Paradise. It’s not necessary to believe in these concepts to appreciate the story, as is clear from the background reading available online through the links under Sources.

But not far into the poem, Dante is led to the gates of Hell. Blake envisages the scene in the image below right, which is cropped from the one in the middle of the panel shown earlier. Myrone & Concannon (2019) interpret Blake’s depiction as ‘a sublimely terrifying landscape populated by souls trapped in alternating circles of fire and ice … ‘ – the red and blue shards, burning forests and melting glaciers.

The scene arises in Inferno 3, where Virgil explains, in Mandelbaum’s translation, that ‘this miserable way is taken by the sorry souls of those who lived without disgrace and without praise.’ Perhaps these equate to those complacent or indifferent to the world’s state. There’s no escape by sitting on your hands and hoping the world will mend says Dante, and so does Blake.

Taking an hour or two to stroll through Glasgow from hotel to train station, and after stopping for a welcome strong coffee … there it was, a poster stuck on the window of an empty, near-derelict shop on Sauchiehall Street. It showed the globe burning, a red shard not unlike Blake’s.

Sources, Links

Da Vinci

Leonardo Da Vinci. A Life in Drawing. 22 November 2019 to 15 March 2020. Exhibition at the Queen’s Gallery, Holyrood, Edinburgh.

Clayton, Martin. 2019. Leonardo da Vinci, A Life in Drawing. Royal Collection Trust.

Dante

Dante Alighieri. 1300-. The Divine Comedy, The Vision of Paradise, Purgatory and Hell. Many translations. Available online via World of Dante (1980 verse translation by Allen Mandelbaum), Poetry in Translation (prose translation by A.S. Cline) or Gutenberg (older, verse by A.S. Cary) the latter with illustration by H. Gustave Dore. Penguin book with verse translation by R. Kirkpatrick (rec.). Further background on the Divine Comedy at Digital Dante and World of Dante (link above).

Blake

Myrone, Martin; Concannon, Amy. 2019. William Blake (exhibition book). Tate Publishing, London.

Schutze, Sebastian; Terzoli, Maria A. 2019. William Blake, Dante’s Divine Comedy, The Complete Drawings. Taschen: 464 pages.